Building 'human capital'

I'm glad to see a Scientific Research Council-anchored Rural Youth Employment Project advertising for consultancy services to a bee-keeping component.

As usual, the project is funded by external donors, this time USAID and the UNDP. Even the construction of a new headquarter building for our Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Foreign Trade on the Kingston waterfront is being backed by a US$15-million grant by the Chinese government. Now, that's one government that the Jamaican Government is going to find it hard to say no to in future diplomatic negotiations.

Small as it is, the four-parish rural youth employment project is a good move. It is intended to contribute, the advertisement says, to the reduction of youth unemployment by increasing the ability of youth to access sustainable livelihood options. And this will be achieved through skills and business-development training and increased access to agricultural processing and other facilities.

The project will discover soon enough that most of the youth for which employment is to be created are semiliterate and unskilled, despite virtually all of them being secondary-school graduates.

most reckless wastage

'Human capital' is a term that I rather dislike but it will do for the present moment. This country has engaged in the most reckless wastage of human capital, which borders on the criminal. A couple of weeks ago, educators and business leaders, in a Gleaner Editors' Forum with recipients of the 2010 Honour Awards, were bemoaning this wastage of human capital and its consequences for national development. The consequences for personal achievement must not be missed. They are equally horrendous.

President of the Private Sector Organisation of Jamaica (PSOJ), Joseph M. Matalon, told the forum, "clearly, when you look at the statistics coming out of the educational sector, and the extent to which, for example, kids leaving high school at 16 and 17 years of age are barely able to read and write, and are barely numerate, that is not providing a solid foundation for workforce development."

And those statistics are abundant, although I haven't got the capacity at the moment to chase them up: The Grade Four Literacy Test is providing a window on literacy competency in middle primary school. The Grade Six Achievement Test, particularly the core English and Math average scores, sitting in the middle-fifties per cent, is indicating a vast under-performance at the end of primary education.

The vast majority of those exiting secondary education, which is now well-nigh universal, some 85 per cent, do so without the minimum number of The Caribbean Secondary Education Certificate (CSEC) passes for entry into tertiary education or the job market as start-up professional workers.

The Prime Minister himself was recently reminding us that three-quarters of the population has no skills certification, despite the HEART Trust/NTA being around since 1982 and specifically created to address the lack of education and skills among secondary-school graduates.

But, actually, the education system is functioning quite well to its historical purpose of being a massive sieve, sieving out the majority as rejects and allowing only a small elite to advance to the top.

When we step around the deceptive technicalities of calculating unemployment levels in the country, it is starkly evident that the majority of Jamaicans of working age are unemployed, under-employed, or only marginally productive in full employment. The stagnation and decline of productivity, for decades running, provides heavy empirical support for that last point.

critical factors

Although, in fairness, as Prime Minister Golding pointed out recently, productivity is not purely a labour or human-capital factor. The incapacity of businesses to retool, to innovate and to absorb innovation in a stifling economic environment, which is largely the creation of mis-governance, is a set of critical factors of low productivity.

But if you think businesses are low in productivity, consider the non-businesses operated by more than 200,000 small farmers, most of whom are illiterate or only semi-literate, and doing it pretty much the same way their grandparents did it, and with the same results of marginal returns for a massive outpouring of sweat.

And tens of thousands of able-bodied Jamaicans are locked up in idleness in garrison culture and community. It is not just the unemployment which has created the conditions for the garrison, the garrison has also created the conditions for the unemployment.

Clearly, some radical thinking has to be done and some radical action taken to make human capital more productive and less wasted in this country. Education has an important role to play. But, as I will discuss later, part of the problem of human-capital development may be overplaying the role of education.

The Grade Seven 'stop them in their tracks' Literacy Programme, aimed at curing illiteracy at the entry point into secondary education, which was recently unveiled by the Education Ministry is a good move in the right direction. The most important educational achievement for human-capital development is simply literacy, broadly defined as acquiring the basic tools for further formal learning and social and economic engagement.

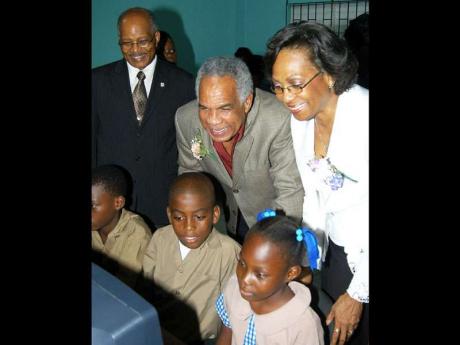

More interventions like the South St Andrew Literacy Programme have to be done. With the support of MP Omar Davies, who, as minister of finance, sensibly proposed that the country calculates return on investment for expenditure on education, the programme has assisted thousands of students in the schools of the constituency over the last 10 years.

When the programme started, only about 20 students from South St Andrew were being placed in traditional high schools each year. In the second year, the number jumped to 47 and more than 100 secured traditional high-school places in the third year. At the Iris Gelly Primary School, more than 70 per cent of the students were deemed to be at risk when the intervention was launched. That proportion was pushed down to 16 per cent by year three.

Tracked through high school, CXC passes have risen dramatically. Among students who were assessed as been unable to read at the start of the intervention, 57 went on to sixth form and 50 of them enrolled in tertiary institutions including overseas ones.

Robert Lalah's feature story in The Gleaner last Tuesday, 'The power of intervention', didn't give the base numbers from which percentage changes could be calculated, since he didn't do the calculations himself.

a top priority

I want to warn and advise the minister and Ministry of Education again that an elaborate Literacy Improvement Programme, with trained 'specialists' assigned to schools, is not the way to go. Every primary school teacher must be quickly made a literacy 'specialist'. That is what teacher education in college should have done, in any case. Her job, on which hire and fire decisions should be made, must be making the children literate. And the support resources should be made available as a top priority.

Literacy education is easy and comparatively cheap and provides absolutely the best return on investment in education. Within a single year, the South St Andrew schools of poor-performance students were showing pretty dramatic turnaround results.

But education isn't everything. There needs to be some radical interventions for as is, where is, building of human capital and increasing human-capital productivity. We are spending comparatively too much on (formal) education while neglecting investment in areas of creating employment and business opportunities, in skills building by apprenticeship, and in the delivery of extension services in various fields of production to provide directly useable technical knowledge to people.

There are massive remediation costs in our pretentious six-for-a-nine education system, which is refusing to get the foundations right. Those at the top end of the system, who are most able to invest in their own personal human-capital development, should pay more, freeing up resources for alternative uses in and out of education.

The fact of the matter is that when economies grow, as is, where is, the demand for education output naturally increases and the means of paying for it , by both individuals and the state, also increases.

Actually, I am liking the term 'human capital' a little better now. The purpose of capital is for investment to produce something at profit. Money in the bank is not productive capital. There is a powerful and largely unchallenged education myth, pushed by the education system, and bought by political leadership and the public, almost universally, that if people are educated (like savings) then somehow those savings will make their way into becoming productive capital.

Deployment of savings as productive capital, i.e. as money producing something, requires a whole set of other things besides the availability of the money itself. We note, in passing two salient facts to the matter: 85 per cent of our tertiary-level educated human 'capital' migrates, and a vast amount of money has been parked in high-yield government paper without becoming capital producing anything.

A bold government, ashamed of the waste of human capital and penitent for facilitating this most massive waste of resources in this country, and determined to do something about it, will move to build more programmes like the Rural Youth Employment Programme, but on a far greater scale, even while improving the productivity of the state-education system.

Martin Henry is a communications consultant. Feedback may be sent to medhen@gmail.com or columns@gleanerjm.com.

But education isn't everything. There needs to be some radical interventions for as is, where is, building of human capital and increasing human-capital productivity.